Key Takeaways

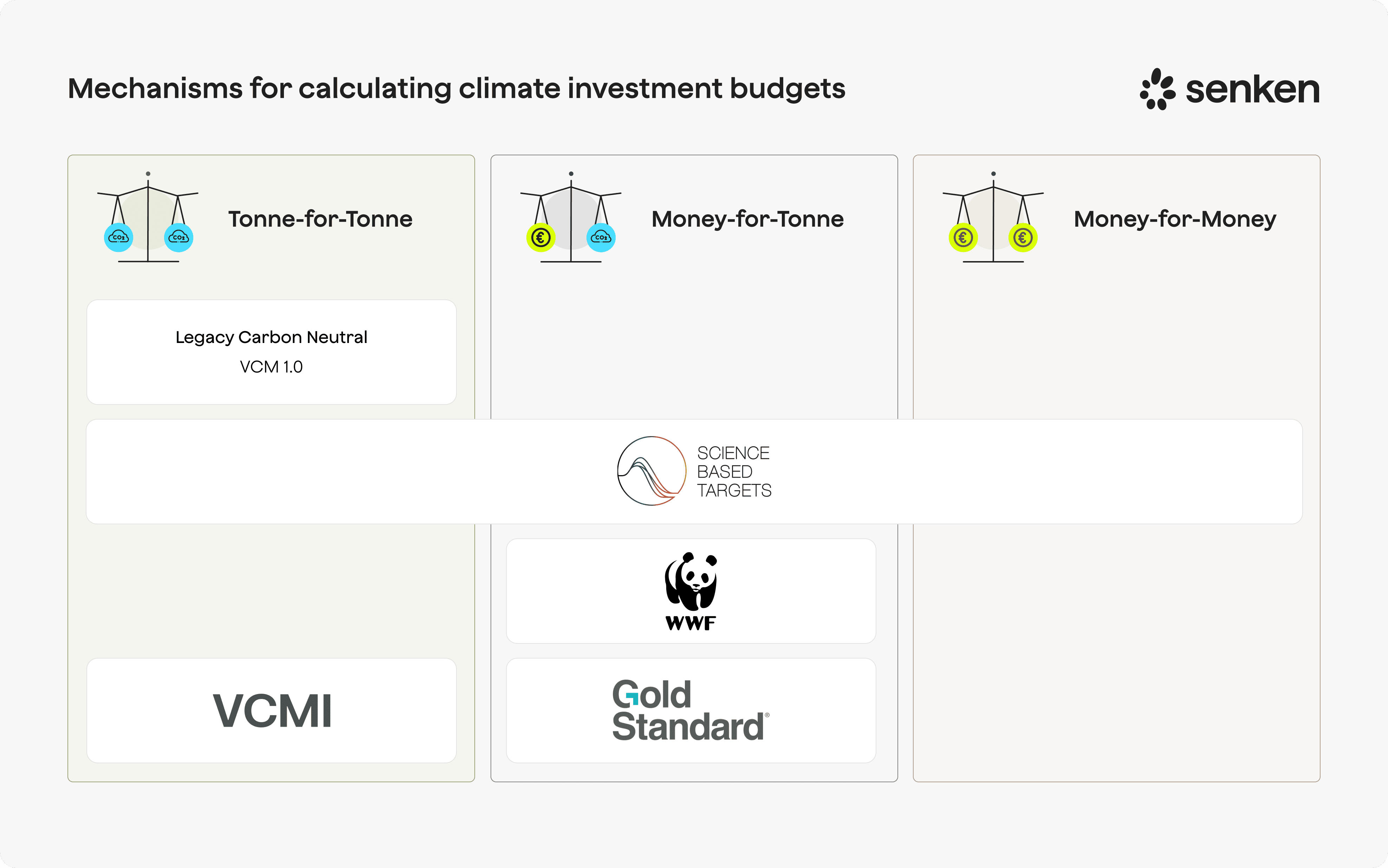

- There are three methods in which your company can determine your budget for expenditure on carbon credits. These are the Tonne-for-Tonne, Money-for-Tonne and Money-for-Money approaches.

- The tonne-for-tonne method is still widely regarded as the go-to-approach, since it ensures direct link between emissions and mitigation efforts in terms of CO2e, and is useful for compensating for your residual emissions on the way to net zero. The “VCM 2.0” that is starting to formulate, is heading towards a more contribution focused approach, through the money-for-tonne method.

- The money-for-tonne method generates a budget that can be spent on emissions reduction initiatives and external climate projects by allocating an internal carbon price on its scope 1-2 and scope 3 emissions. This aids in assigning a monetary value to each ton of carbon emissions to evaluate the potential cost/benefit of emissions reduction strategies.

- The tonne-for-tonne method operates on the principle that for every tonne of CO2 emissions produced, an equivalent amount of carbon credits must be purchased. These credits represent the reduction or removal of the same quantity of CO2 elsewhere.

Intro

Companies invest in carbon credit projects in the VCM to offset their unavoidable emissions so that they can address net zero targets effectively. Knowing how to assign a monetary value to environmental impact comes with its challenges, and there are three main approaches in the market that can help companies with this:

- Tonne-for-Tonne

- Money-for-Tonne

- Money-for-Money

Understanding how these three approaches work is critical for carbon credit buyers who wish to be aware of the true impact of their investments. This chapter breaks down each of the approaches, helping you understand the pros and cons of each.

Tonne-for-Tonne

To accurately assess the impact of a company's investment in climate projects, the mainstream practice involves measuring CO2 removal and avoidance, following the tonne-for-tonne approach.

The tonne-for-tonne approach in carbon markets refers to a method of offsetting carbon emissions where each tonne of CO2 emitted by a company or entity is matched by an equivalent ton of CO2 removed or avoided through verified carbon offset projects. This ensures a direct balance between emissions and offsets, aiming for a net-zero impact on the atmosphere.

This approach enables companies and project developers to reliably report on the amount of GHG emissions a project has either passively avoided or actively removed from the atmosphere. These measurements are crucial for demonstrating the effectiveness of climate initiatives and for validating corporate claims about their contributions to climate change mitigation.

By adhering to CO2 measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) frameworks, companies can confidently claim their investments contribute to climate change mitigation. These frameworks provide standardised methods for tracking and reporting emissions reductions, ensuring transparency and accountability. Companies can also incorporate the CO2 avoided or reduced into their GHG offsetting targets, aiding the achievement of their Net Zero and Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) aligned goals. This integration helps companies demonstrate their commitment to long-term sustainability and climate responsibility.

Despite the positive and proven effects of CO2 removal and avoidance projects on climate mitigation, climate impact extends beyond GHG emissions. Many projects, even with low CO2 avoidance or reduction capacity, yield significant co-benefits through improved water tables, enhanced microclimates, biodiversity and habitat preservation, and other ecosystem services, as well as innovative technologies. These projects contribute to broader environmental health and resilience, offering benefits that support sustainable ecosystems and communities as well as covering SDGs.

This is why it is worth exploring alternative methods for companies to offset CO2 emissions while supporting projects that generate additional impacts beyond CO2.

Money-for-Tonne

An example of another common method for assessing climate impact is the Money-for-Tonne approach, which involves companies setting an internal carbon price to estimate potential climate risks related to increased CO2 emissions. The carbon price helps establish an internal carbon fee, which creates a dedicated budget for climate mitigation projects. This approach allows companies to directly link their financial decisions to their climate impact, encouraging more responsible and impactful investment.

The Money-for-Tonne approach links beyond value chain mitigation to a specific percentage of a company’s emissions, aiming for annual mitigation equivalent to 100% of Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions.

The fee can vary between emissions directly controlled by the company (e.g., Scopes 1-2, and travel emissions) and those where responsibility is shared (the remainder of Scope 3). This differentiation can be achieved by charging different fees for upstream and downstream Scope 3 emissions, reflecting the varying levels of control and influence a company has over these emissions sources. Fees can be set based on the company's shadow price, implicit price, or abatement costs.

An example of a Money-for-tonne approach can be found when looking at the global payment provider Klarna, who have set a fee of $100 per tonne on their Scope 1, 2, and travel emissions, and $10 per tonne for the rest of Scope 3 emissions. From 2021 to 2024, the fees generated over $5 million, which were allocated to projects within the fund.

The Money-for-tonne approach has several advantages, such as supporting projects with significant climate mitigation potential beyond CO2 and fostering the development of innovative removal technologies, and therefor showing more ambitious commitment to climate action. This method encourages investment in diverse projects that address multiple aspects of environmental sustainability. However, there are downsides, such as the risk of setting the carbon tax too low or disproportionate to a business's revenue and sustainability strategy, potentially leading to greenwashing.

Thus, it is good practice for companies adopting this approach to be well-progressed in implementing their sustainability strategy and to follow the mitigation hierarchy by prioritising avoidance and reduction before offsetting remaining emissions. This ensures a comprehensive and responsible approach to climate action.

Money-for-Money approach

The third common approach is to make use of the "money-for-money" strategy, which involves companies designating a portion of their revenue or profits specifically to fund activities beyond their value chain mitigation efforts, such as projects that focus on Co-benefits rather than CO2 avoidance and reduction. This often includes investing in emerging carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies, or pure conservation initiatives without expecting strict quantifiable returns in CO2. For this reason the Money for Money approach can be compared to pure Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) investments as part of a company’s Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) strategy. In other words, similar to corporate to philanthropic contributions.

However, this method lacks a direct link between a company's emissions and their contribution amount, diminishing the incentive to reduce internal emissions and assigning an arbitrary value to the dedicated budget. Consequently, it is less precise than an internal carbon fee, as it separates the company’s responsibility to lower CO2e emissions from the potential negative consequences of ignoring this value, known as the social cost of carbon. Despite this, it is recommended for large emitters that need to focus on reducing their own emissions and struggle to set a credible carbon fee for external projects.

The money-for-money approach involves companies allocating part of their revenue or profit to support external mitigation efforts, including emerging CDR technologies, but it lacks a direct link to their emissions, reducing the incentive to cut internal emissions.

Summary of the three approaches: Money-for-Tonne, Money-for-Money, and Tonne-for-Tonne.

Approach Definition Pros Cons Tonne-for-Tonne 1 tonne CO2 = 1 Carbon Credit- Traditional way of determining responsibility

In conclusion, each approach changes the way companies chose to support projects that deliver climate impact, moving beyond the rigid and in some cases overly complex structures of CO2 avoidance and reduction methods and allowing them to support projects that are limited in estimating their positive climate impact through CO2 emissions .

Similar to the Science Based Targets initiative's (SBTi) Beyond Value Chain Mitigation (BVCM) efforts, the money-for-tonne and money-for-money strategies enable companies to mitigate the risks associated with unforeseen issues in CO2 avoidance or removal calculations, due to risks brought by the complex number of variables needed to precisely account for CO2. This flexibility allows companies to back projects that demonstrate impacts that go beyond purely greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions.

Senken is fully equipped to assist your organisation in identifying and supporting high-quality projects, regardless of the approach your company chooses to follow. Contact us for assistance with selecting top-rated carbon credit projects to meet your climate targets.

Below you may can see the various guidelines and frameworks such as those offered by the VCMI, SBTi and the WWF aligns with the 3 mechanisms:

Again, it is important to note that the approach taken, depends heavily on your companies sustainability strategy. We will break down this train of thought in the next chapter.

.svg)